Looped |

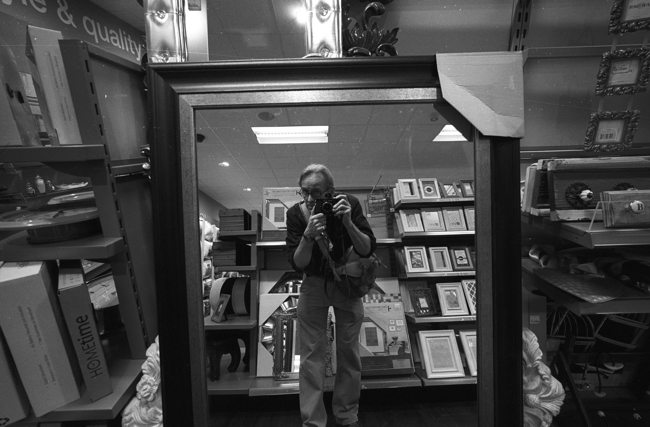

Self portrait in TK-MAXX Hereford. What else is there to do?

'Looping' is a form of imprisonment that the Chronoguard use in the Thursday Next books. The idea goes that you are imprisoned in a fixed loop in time. This might be two minutes for the worst offender, an hour for white collar crime, more if you have a good lawyer. TX-Maxx is actually the prison where this happens, an outlet for remainder garments, cheap mirrors and woks being the cover story. I wrote this for two reasons. Firstly I wanted to consolidate my ideas of being looped which I thought was a neat idea, and secondly, I wanted to tell a story in 2nd person narrative. Of the two, the second became the most effective. It's not been published before.

The technical term was 'Closed Loop Temporal Field Containment' but to everyone who had been so incarcerated, it was known as Looping. You were a looper, you had been looped. The period of time in which you found yourself was a loop. The company that managed the system on behalf of the Chronoguard was named Loop, Inc. Loop, loop, loop. Which was what you did these days: Same sixteen minutes of time, exact same place, exact same people. You can explain to others what's happened to you, but success is short lived. Even if someone does believe you, it will never be for very long. Inside the loop those sixteen minutes are all you have; Outside the loop those sixteen are simply an empty block of time that to most people was utterly unremarkable and have now long receded into the dim forgotten past. Cruel and Unusual? Sure? Effective? Youbetcha. "Will Sir be having a dessert today?" asked the waitress, taking away your plates. She was young and pretty and had a kindly face. She served me nearly twenty-five thousand times. I told her my name every single time. She hadn't remembered once. She couldn't remember. There was any number of her, but only one of me. Anything you had on with you, stayed with you, anything you put down was lost into Chronoclastic ether next time the loop was reset. You changed clothes, washed, ate, drank, disposed of waste - everything was supplied accessible within the temporal window they gave you. That's why loops were generally centred around shopping malls with a food court and public restrooms. It wouldn't take you long to starve, stuck inside sixteen minutes, in say, the middle of the Atlas Mountains. When you arrive at Loop=1, you first find a notebook and pen to log the number of Loops, the equivalent of chalk marks on the wall of the cell. You have no money, but you can steal what you want, because your punishment for a world in which there are consequences is to be banished to a world where there are none. The irony and perversity are not wasted on you. You try using the phone, but there's no-one to call that can help you, nor believe you. The people you call think you're a crank or a hoax caller, and you're reset every sixteen minutes, so it's like it never happened. You even try calling your past self to figure out a work around, but your past self is only eleven. Whatever happens in the Loop, stays in the Loop. You shout and cry and carry on until Loop=20, and then you calm down. You start to explore, and by Loop=450 you have a general understanding of the parameters of your prison. The date, the time, where to find food, nearest toilets, bookshop, that kind of thing. By Loop=1000 you will have extended that particular knowledge to more usefully reflect your own particular needs. Who will be kind, who will not, who you can talk to, who can be relied upon to perform a physical act at short notice on credit. At Loop=2,500 you have your first visit. Your caseworker, wanting to know how you're settling in. They don't know because you're not observed. Even if they could, there's no need. What you are doing, you're doing in the distant past. If there was a ripple in the Standard History Eventline they'd know about it, but there is nothing. In these sixteen marooning minutes, fixed somewhere in a backwater of the 1990's, you're temporally insignificant. A very small pebble in a pond with much larger, more recent and more relevant ripples. Your Caseworker won't stay for long; just to tick a few boxes and move on to the next parcel of time. You ask him for outside news. "There's no news," he says, "this is 1996. Everything you ever did, all the wrong you've ever done, all the happiness you've ever had - it hasn't happened yet." "Then I haven't actually committed a crime either." "Not yet," he agrees cheerfully, "but you will, and with 100% certainty. If it's in the Standard History Eventline - which it is - it will happen, it did happen, it has happened. The fact that you're here proves it." The logic isn't totally sound, but then in the time industry, it rarely is. "Has my lawyer lodged an appeal?" The caseworker pointed to a pram the other side of the food court. "That's your lawyer. She doesn't even know she's going to be a lawyer. Take it up with her." He was bluffing. The toddler's name was Charlotte. Her mother was Keilly, waiting for an old friend from school who was having a hard time. Good person on the whole, doing the best she could. By Loop=5,000 you've pushed the geographical boundaries of your prison, and discovered just how far you can get in your minutes. You could catch a bus or a train or even a cab - but the furthest you can get, furthest you ever got, was on a stolen motorcycle. Not the most powerful you could find but the fastest within the shortest time frame. You get almost twelve miles out of town to the South, but your time runs out within sight of the cast iron road bridge. And no matter what you do, you can't change that. You challenge yourself, you practice endlessly, you push too hard and you die in the attempt. It's painful, but you come back, right as rain, just with a scuffed coat. No matter what you try, you never cross the bridge; it is the limit of your time and space. It's the horizon you can't ever cross. By Loop=10,000 you're starting to get weird, and angry, and desperate. You stop logging how many loops you've been in, and you kill yourself for the first time, then, when that doesn't satisfy, you kill someone else. Someone you didn't like to begin with, then just random people. But you don't actually kill anyone or at least, not for very long. You may go on an orgy of violence just then, and work through your fury in a hundred or so Loops until you calm down and start to log your loops again. By Loop= 20,000 you'll have been Looped for over six months, and pretty much every sound, movement and scent will be familiar to you. You can predict what people will say, what people will do. You start to relax, read books, sketch, learn a musical instrument. You start to count how many loops to go, rather than how many have been. 822,654 or thereabouts, about twenty-two years in sixteen minute hexitemporal segments. A couple of days later, when the subtracted Loops don't seem to be making much of a dent from your tally, you go back to counting up again, and life gets back to normal. You start talking about yourself in the second person. You're not sure why. You eat, you sleep, you shit, you wash, you exercise. You are Looped. You are relooped, you are relooped again. Again, and again, and again. "Will Sir be having a dessert today?" asked the same waitress, taking away your plates and smiling in a friendly yet mechanical manner. You usually ate here and always the same - a ready made burger that you divert to your table using some pretext or other. You've become connected to the waitress, but she doesn't know it. You know her name, and what her mother thinks of her new boyfriend. Little by little you get to know everything about her, but she knows nothing of you. To her, you were just one more faceless customer on an unremarkable Wednesday late in the Summer of 1998. You don't know how her life turns out. "Time is short," you say, "but thanks anyway." "I'll get the check." She doesn't have time to get the check but you knew she wouldn't. The world resets to the beginning of the loop. You are back outside in the car park, the place and time where your loop always begin. You have a generic car key in your pocket but the car park is large. Every tenth loop you search for the car you arrived in, but you have yet to have any luck. It wasn't in the multi-storey, nor any of the open air car parks. You are slowly working your way through all the parked cars, but it will take some time. Hereford is a big place. That's when Quinn arrives. You haven't seen him since your trial. He won, you didn't. "Hello Algy." Anything remotely new in the sixteen is so utterly alien that it leaps out at you like a chainsaw on full power. You jump. "Sorry," says Quinn, looking around, "can we talk?" You know it is a dumb question. Of course you want to talk. You go to a cafe and he orders tea. Prosecutors never order coffee. He asks how it's going. "It's kind of samey," you reply, trying to be sarcastic. He asks if you're past the Berzerker stage and you say that you are. "How many did you kill?" "Eight, I think. I wasn't really counting." "It gets tiresome, doesn't it?" "Yes," you say, "and messy, and pointless. What do you want?" "We want to know who was responsible. Who gave you the access codes, whose bright idea it was to go trolling around the middle ages. Most of all, how you all got past the 1720 pinch point without setting off every trembler at head office. That could be real useful to us." You tell him you flashed through during the monthly telemetry squirt from the Renaissance, but you know he knows this. What he actually wants is the gold. Taking that much historical gold destabilised the commodity markets in the early history of banking. And banking doesn't like to have its history pissed around with. The ripples cause crashes. Our heist has already been blamed for two depressions, the crash of 2008 and some inexplicable currency variations. Historical gold is a good moderator. You want financial stability? Flood the past with gold. lots of it. "Where's the gold?" You tell him it's in the Holocene. "The Holocene is a big place," he says, "you need to be more specific." You tell him you never knew where the gold went. That only Kitty knew. "Kitty says that you know." "Kitty's lying." "One of you is." "I was only a small cog," you tell him, "blinded by cash and the misplaced hubris of down-streaming. I'd never done the middle ages before. Kitty asked me to join her. I was ... flattered." Quinn takes a deep breath. Your sixteen minutes were up long ago and you haven't reset. That's what happens when they drop someone into your Loop. You hear new stuff, see things that hadn't happened, like you're watching a new sequel to a film you're very familiar with. "Last word?" asked Quinn. "Last word." And you are back at the multi-storey, Loop=42,001. All the players have reset themselves to their start positions. The kid on the bicycle, the balloon seller, the harassed father with the two unruly kids, the busker with the accordion. The same sixteen minute section all over again. You look for your car, and you don't find it. You give up at Loop=61,200, and never look again. You're hungry again and go and find the waitress. The burger tastes the same. It should do; it's the same one. You try out a joke you found in a book in Waterstone's. You think she will laugh, and she does. You know her sense of humour. You know her. At Loop=150,000, you have an intimate knowledge of most of the town and everyone in it. Even so, you systematically search out and take fascination in anything that is new or unfamiliar. You find a new street, or knock on a door you've never knocked on before, or find your way to a room you never knew existed, with a person you've never seen. You visit the same place for the next ten loops, learn everything to be learned, then move on. Everything that happened within that sixteen minutes, you are an expert upon. It is an expertise of the narrowest of fields. At Loop=200,000 Quinn visits again. You expect he will because 200,000 is a nice round multiple of sixteen, and the Time Engines work on a Hexadecimal architecture. "Back so soon?" you ask, still being sarcastic. Quinn doesn't do sarcasm, you realise. "We need you to turn Kitty," he says, and shows you an agreement from the DA. If you could find out where and when in the Holocene the gold is hidden, you could expect to be out 100,000 loops earlier. You hold out for 200,000, and get it. You sign the agreement, and ask where she is. "Where she's always been, ten minutes North." You know this is unusual. Loops were designed never to overlap geographically or temporally. Intersections gave convicts potential areas of conflict with other prisoners. Quinn tells you to make it look like a chance meeting. You drive out North on the same motorcycle you used to try and reach the bridge. It takes you until Loop=200,032 before you spot her, and she you. It's not hard. Anything that is at variance to the rigidity of the timeline stands out like a flashing beacon. You drive past one another on the road, you both stamp on the brakes and then back up. "Algy?" she says. You say hello. She doesn't look very happy. It was her gig, after all. You were just the muscle. You find that the maximum amount of time you can spend together is one minute and nine seconds before you both get reset to the head of your loops. You tell her about Quinn's deal straight away. She is not surprised. "He asked to find out the same from you." She says she doesn't know where the gold is but you know that, because you knew where the gold was all along. All seventeen tons of it, lying in the open on the edge of a bay that fifteen thousand years later will be in the Derry peninsula. It's still there, in the back garden of Mr and Mrs Tyrone, under eight feet of accreted soil and peat. They have barbecues over it, with their friends. Over the next 300 loops you try and rebuild your relationship with Kitty, but all she wants to know is about the gold. You come to realise there was never a relationship. You think you might tell her, but you don't. There's nothing to be gained from it. "You're not going to tell me, are you?" she says finally. "No." You don't meet her again. You turn back to the waitress in the burger joint. She has a delightful gurgle of a laugh. You find yourself in love. Quinn returns at Loop = 260,000. You tell him Kitty doesn't know where the gold is, or if she does, she's not telling. "You're both a bunch of time wasters," says Quinn, not realising the irony of his words, "enjoy your time." You go back to your sixteen minutes loops, over and over again. Another year's worth of sixteens go by. It's never the time, it's the repetition. There is not a book you haven't read, not a person you haven't spoken to. You've been served by the waitress over a hundred thousand times, and when Quinn reappears at Loop=320,000, you do the deal, but for a full pardon. You are one third of the way through your sentence. To be the eighteenth richest person on the planet, you thought you could last out. "Everyone comes to their senses eventually," says Quinn. "If the gold is where you say it is, it'll be time served." It is your final loop, the only one that will have any lasting consequence upon the townsfolk around you. Pointlessly, you say your goodbyes to people who have met you only a few minutes before. To them it's just plain weird, but to you it means more than you know how to express. The man in the corner store who was always cheery, the busker who played the accordion in the main square. Most of all, the waitress. You feel emotional speaking to her. You make her laugh again and hand her your address on a scrap of paper. "O-kay," she says, somewhat uneasily. You have a speech, and it's a good one because you've had ten years to write it. She stares at you as you speak and raises an eyebrow. You know that no-one has ever understood her so well, no-one has ever encapsulated what she needs in words of such poetry and power. You'll know she'll remember you. But it's not to meet in the 1990's. It's to meet you back here in twenty-seven years, if things haven't worked out. There would be no point in getting her to meet you earlier; you wouldn't know her. Besides, you're only eleven. And that's where you are now, in a much-changed market town, the shop fronts modernised, the clothes different, shoppers clutching smart phones, going about their business. You've been out for a couple of days. You don't have a job and you don't have much money. But you have liberty, and the sixteen minutes you've just witnessed has faded gloriously and without ceremony into the past. There have been 8356 different sixteen minutes since your release. It's a hard habit to break. You'll be counting your sixteens for at least another six months. You glance at your watch and wonder if she will turn up, always supposing things didn't work out for her. You hope they did, of course. You're still waiting. |