Orphaned Prose: The Eyre Affair original 1st Chapter |

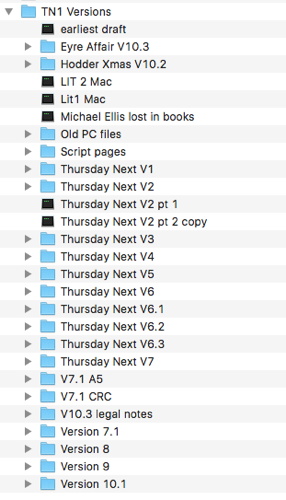

The version log from the exhaustive, four year writing spree that resulted in The Eyre Affair. V6.2 equates to about 1995 just before I went Mac - all of these files were originally written on Clarisworks (remember that?) but now open only on BBedit. Note 'Lit2 and 'Lit1' files, which was when TEA was called 'The Litera'tecs'. Michael Ellis Lost in Books was a short story that preceded the core idea that became The Eyre Affair. There is a lot more about the writing of The Eyre Affair on other parts of my website (You can go to The Question House and word search 'Thursday' if you so wish) But I've often told stories - and given advice to writers - that you should write your book, then chop off the first chapter, farm out any expositional facts to chapters 1 - 4, and then feather over the cracks. I was writing without access to advice or writer's workshops and going merrily ignorant on my way, sort of discovering things as I went. This doesn't make me special, it makes one realise that storytelling is very much an intuitive dark art. We can all tell a story; telling it better takes a bit of time to figure out. This was the original first chapter, before one of my sporadic rewrites. It's fairly 'draggy on the eyes' (AKA boring) and stuffed full of painful exposition, so you can see why it had to come out, but anyone recently acquainted with TEA will see scraps that ended up in the book; the 'authorship question' subplot for one, and note that Pickwick the Dodo was not yet in - her place was originally taken up by Elmo the cat. Landen is a successful writer, too - but that changed, as did Thursday's nature. Here she seems weaker, and less the captain of her own destiny. Reading it now makes me wonder how anything worthwhile came out of this at all - a lot of time and judicious editing, I think - but mostly time. There wasn't a presentable draft of TEA until four years after this initial section was swept away. Have a look - if you dare. I'm not kidding over the 'boring' description. |

With the Baconians |

'...The Special Operations Network was instigated in 1965 to relieve an overworked police force from the special duties that particular areas of policing required. There were 30 departments in all, starting at the more mundane Criminal Truancy (SO-30), Literary Detectives (SO-27) to Animal rights (SO-24). Anything below SO-20 was restricted information although it is common knowledge that the ChronoCops were SO-12 and anti-terrorism SO-9. It was rumoured that SO-1 is the department that polices the SpecOps themselves. Quite what the others do is anyone's guess. What is known is that the individual operatives themselves are mostly ex-military or ex-police and slightly unbalanced. If you want to be a SpecOp, the saying goes, act kinda weird....' Millon De Floss - A short history of The Special Operations Network |

The job, they say, ages you - and it had aged Filbert a lot. In the eighteen months we had been going out he had aged ten years. From a lively man in his late twenties he had worn in front of my eyes, contracted all sorts of aches and pains and grown more reactionary in his opinions and outlooks. I guess it happens to us all so gradually that we never notice; being an old fart just creeps up on you and then - pow! your body's headed south, you're whinging about the price of cat food, you laugh less and the prospect of birching young offenders starts to fill you with less revulsion than it used to. Filbert Snood went away on an assignment to Tewkesbury and never came back. I had a call from his commanding officer explaining that he had been 'unavoidably detained' during assignment. It was ChronoCop talk for an accident but I didn't know that then. I thought he had met another girl in Tewkesbury and didn't have the balls to tell me. No, I didn't discover what had really happened until much later, when the crazy Hades thing started up and my return to Swindon. It hurt at the time but I hadn't been in love with Filbert. I was certain of that because I had been in love with Landen. When you've been there you know it, like seeing a Monet or going for a walk on the west coast of Ireland. My love had a yardstick and that yardstick was a one-legged writer ten years my senior: Landen Parke-Laine. I'd denied the feelings, of course. The fact that a month didn't go by without me thinking of Landen should have been an indication, but denial is a strong emotion - and seeing his works on sale in almost every book shop was enough of a reminder. He sent me pre-publicatfion copies of everything he wrote. I left them untouched with his monthly letters, afraid that opening them might open old wounds too. I was what we called an 'Operative Grade II' for SO-27, the Literary Detective division of the Special Operations Network based in London. Since 1980 the big criminal gangs had moved in on the lucrative literary market and we had much to do with little funds to do it. I worked under Area Chief Boswell, a small puffy man who looked like the Pillsbury doughboy. He sweated a lot and lived and breathed the job. I never heard of him ever taking a holiday, although I understand he did take time off to have four children, so he couldn't have been in the office all the time. It was with Boswell that our department arrested the gang that was stealing and selling Ben Johnson first editions to order and also the uncovering o[f an attempt to forge a copy of Shakespeare's lost work, Cardenio. Fun whilst it lasted but only small islands of excitement amongst the ocean of day-to-day mundanities that is SO-27 work: We spent most of our time dealing with illegal traders, copyright infringements and fraud. I had been with Boswell and SO-27 for eight years, living in a bedsit in Maida Vale with Elmo, a blue Abyssinian with an unruly manner and cobalt eyes. I was desperate to get away from the LiteraTecs but promotion was pretty much a non-starter; I was in dead-women's patent-leather shoes, tipped for the next rung as soon as someone moved on, but it never seemed to happen. Susie Flanagan was my immediate superior but she made no signs of moving on or moving out, despite repeated engagements where Mr Right turned out to be either Mr Liar, Mr Drunk or Mr Already-Married. I was desperate for a change, so when the Anti-Terrorist branch of the Special Operations Network asked for volunteers from the Literary Detective divisions to go undercover for them, I had almost bitten off their arm. So that was pretty much why I was doing what I was doing and where I was doing it at this moment in time: plodding the streets in North London as an undercover Baconian, attending meetings, raising cash and doorstepping - trying to induct a gullible member of the public into believing that Francis Bacon actually penned the plays of William Shakespeare. I was thirty-six and it was Summer, 1985. The area that the local Baconian group had given me was around Derwent Vale, a collection of pretty tree-lined streets of typically British pre-war semi-detached houses>. I walked past the neat garden and confidently rang the bell. 'Hello!' I said brightly to a middle-aged man who opened the door. 'Yes?' he asked suspiciously. 'My name's Thursday Next,' I told him, 'I'm a member of the Baconians.' I handed the battered ID across to the man who looked at it and then handed it back. 'You looked better with short hair.' 'Do you think so?' 'I'm very busy-. 'It won't take long. Have you ever stopped to wonder whether it was really William Shakespeare who penned all those wonderful plays?' The homeowner thought for a moment. 'If you expect me to believe that a lawyer wrote A Midsummer Nights Dream, I must be dafter than I look.' I wasn't going to be put off. In fact, in a sort of perverse way, I kind of enjoyed arguing a lost cause. It reminded me of debating club at school, where you were instructed to argue in favour of collaborators. As I recall, I did fairly well. 'Yes,' I continued, 'but don't you think it might be something of a gross miscarriage of justice that the true author of these fine works might not be getting the credit he was due?' He just stared at me. I sighed and said: 'I'm wasting my time, aren't I?' 'I'm afraid you are.' The door shut in my face again. It was a common occurrence. I walked back out to the road and sat down at a tram stop. It was lunchtime and I had d=one three streets. Out of two hundred and thirty six houses I had had seventy three no-shows, sixty five slammed doors, ninety-six polite 'thanks-but-no-thanks' and two people who were interested in hearing what I had to say. One of these was probably more interested in me than Bacon as I caught him trying to sneak a look down my cleavage, but two out of nearly two hundred and fifty was good by Baconian standards. Not even the Kit Marlowe Appreciation Society managed that. Ordinarily, Baconian Societies were not illegal organisations at all. Their purpose was to prove that Francis Bacon and not Will Shakespeare penned the greatest plays in the English language. Bacon, they believed, had not been given the recognition that he rightfully deserved and they campaigned tirelessly to redress this supposed injustice. At this level no laws were being broken; the Baconians, whilst misguided, did have every right to their opinions. The trouble began when several hardliners led by a man named Conrad Margetts had broken away into a faction that called themselves the The Bacon Action Committee and embarked on a campaign of direct action against Shakespeare and all things Shakespearean. They had started by picketing theatres and altering the title pages of Shakespeare's works in public libraries. Dismissed as cranks and expelled from the official Baconian societies, they sought broader means to make their grievances felt. Plays were disrupted, TV programmes jammed and the theatre at Stratford daubed with Pro-Bacon slogans. When a group of armed Baconians burst into the Bodleian library and burnt a rare copy of the 1623 First Folio, it was time to act. The anti-terrorist squad of SpecOps-9 was briefed to remove the criminal element and a pitched battle had begun, culminating in several car-bombings in Stratford and the mortar attack on Anne Hathaway's cottage. In the ensuing gunfight two SO-9 operatives lay dead. The stakes had changed and after hunting in vain for Margetts and his thugs, SO-9 decided to recruit SpecOps operatives with literary talents to infiltrate the Bacon Action Committee through the more respected Baconians. After nine months of undercover work without so much as a sniff of Margetts or the Bacon Action Committee, I was still tryingÏ. Another three months of doorstepping and dreary Bacon meetings and SO-9 would replace me; a year, they figured, was long enough for anyone. When the alternative was back to dull authenticating of manuscripts, a year wasn't long enough. I took another bite of my sandwich and budged up as a man sat down beside me. He smelt very strongly of an aftershave that Landen used to wear. I hadn't liked the scent then and I didn't like it now, but fond memories of summer picnics on the white horse at Uffington hove into sight and I allowed myself a shy smile. 'Proust Aftershave' I murmured to myself, but the stranger heard me. 'Sorry, is it that strong?' he asked apologetically. 'I don't know,' I replied, turning to look at him. 'Are you using it as an aftershave or a marinade?' He smiled at me. He was about forty and apart from a missing front tooth was a good-looking man. He was dressed in a suit but the tie was loose at his collar. I guessed he was just out of a meeting somewhere. 'The trams don't run in the middle of the day,' he announced, waving a hand at the timetable affixed to the tram shelter. I showed him my sandwich and he understood. We sat there in silence for a moment, him and I. I carried on eating my sandwich and presently he looked at his watch in an agitated manner. 'No trams during the day, I heard,' I said, returning his smile. 'Locked out.' he explained. 'Locksmith said a half-hour. What are you doing down here? This neighbourhood is usually as dead as flares during 6the day.' 'I'm a Baconian,' I replied, as if that would explain all sorts of aberrant behaviour. 'What a shame,' said the man in a disparaging tone that I didn't much like. In truth I was as much a supporter of Will Shakespeare as the next woman, but his attitude was judgmental and patronising. My indignity was real. I answered: 'Are you telling me that a Warwickshire schoolboy with almost no education could write works that were: not for an age but for all time?' 'There is no evidence that he was without formal education,' replied the stranger, whose expression had become more serious. 'Agreed. But I would argue that the Shakespeare in Stratford was not the same man as the Shakespeare in London.' The stranger leaned forward and listened. I continued my well-rehearsed patter almost automatically. 'The Shakespeare in Stratford was a wealthy grain trader and buying houses when the Shakespeare in London was being pursued by tax collectors for petty sums. The collectors traced him to Sussex on one occasion in 1600 and appear to have gone to great lengths to do so; yet why not take action against him in Stratford?' 'Search me.' I was on a roller now. 'No-one is recorded in Stratford as having any idea of his literary success, he was never known to have bought a book, wrote a letter or indeed do anything apart from being a purveyor of bagged commodities, grain and malt and so forth.' The stranger leant back and frowned. 'So where does Bacon fit into this?' 'Francis Bacon was an Elizabethan lawyer and writer who had been forced into being a lawyer and politician by his family. Since being associated with something like the theatre would be frowned upon, Bacon had to enlist the help of an actor named Shakespeare as his front man.' 'So where's the proof?' 'Both Hall and Marston -both Elizabethan satirists- were firmly of the belief that Bacon was the true author of Venus and Adonis and The Rape of Lucrece. I have a pamphlet here which goes into the matter further. More details are available at all our meetings; we used to meet at the town hall but the Radical Marllovians firebombed us last week. I don't know where we will meet next. But if I can takäe your name and number, we can be in touch.' I looked at him earnestly, fumbled for a pamphlet in my bag and produced it after a struggle. 'Sorry, it's got a bit of tuna on it. Be popular with the cat though. Can I take your name?' 'You can, Miss Next. It's Margetts. With two 'T's'.' My heart jumped. He knew my name. He said Margetts. Coincidence? He didn't look like a crazed bomber and a murderer but I guess they never do. I struggled to keep my thoughts under control. A wrong word now would arse up any chance of arresting him, and I wasn't going to tackle him on my own. 'You know my name,' I replied. 'And you know mine if you read the papers.' 'Conrad Margetts?' He smiled. I lowered my voice and looked around. 'This is an honour, sir. There are many of us in the movement who are in full support of your good work against the upstart crow. Is there any way I can serve you?' It was the reaction he had hoped for. 'You have done military service?' 'Yes sir.' 'And you saw active service in the Crimea?' 'Yes sir.' 'And you were decorated?' My embarrassment was real. I looked down. 'I don't speak of it.' 'I admire humility above much else, Miss Next. I have a favour to ask you.' 'Anything, sir, except, well, you know-' 'It's not for me,' he assured me, 'it's for the cause.' Margetts got to his feet and hailed a Chevrolet van that had been waiting on the corner. 'Let's go.' 'Now?' It wasn't by luck that Margetts had remained at liberty all this time. He wasn't stupid and he didn't take unnecessary risks. To be on the safe side he »assumed everyone he recruited might be an infiltrator. And this meant that from the moment of recruitment to the collaboration in a major crime -something no law enforcement agent could do- the recruited person spoke or made contact with no-one. 'You have a more pressing engagement?' I thought quickly. If I couldn't get a message to my contact at SO-9 then the opportunity would be wasted. 'It's my mother. She's having her veins done at Bart's. I said I'd be there. I can meet you later.' 'Very well,' returned Margetts, opening the door of the van and getting in, 'meet us at the Rose & Crown in Cumberland street in an hour. We'll go from there.' It was a brush off and I knew it. There would be no meeting and probably no Rose & Crown in Cumberland street either. Margetts was careful - with people like me around, he had to be. 'Wait!' I shouted, figuring that this was the closest that SO-9 had ever got to the Bacon Action Committee. A result here would stand me in good stead to find a way out of the drudgery of the LiteraTecs and I was going to take it no matter what. 'I'm in,' I said, 'Take me with you.' He indicated the door and I jumped in. There were two other passengers in the back - a man and a woman- and they nodded to me respectfully. 'Search her.' ordered Margetts and the woman expertly ran her hands over me. 'She's clean.' 'Good. Welcome to the BAC, Miss Next. In the back you'll find Rogers and Grant. The driver is Greene. He hates Shakespeare as much as anyone I know. He'll be your keeper this evening.' We drove on in silence for some time, my mind absorbed with the problem of contacting Lieutenant Porkins at SO-9. If I couldn't get to a phone I was a waste of space to SO-9 and all that they were trying to do. We bumped over a kerb and drove into an empty industrial unit that I recognised just West of Platt's lane. Three more members of the BAC were waiting for us and they were all introduced to me. I learnt that the driver, Greene, had led the attack on Anne Hathaway's cottage but he wasn't in it for Francis Bacon. He just liked destroying things. He looked at me oddly and I felt a vague and unsettling feeling of recognition. If I had busted him in the past, I hoped he was in a forgiving mood. Margetts started to outline the plan of the strike. Grant had been recruited that day like me, but Green and Rogers had been hardcore BAC for a number of years. 'I'm sorry about the secrecy, Ladies and Gentlemen,' announced Margetts, 'but I understand that SO-9 are actively trying to recruit Baconians to rat upon their own.' I knew about this too. It would be suspicious to be seen doing nothing, so SO-9 had been clumsily attempting to turn leading Baconians. They had hoped that this would take the suspicions away from field agents like myself who were in much deeper. 'Bastards!' I murmured, thinking of Miss Klaar -a sadistic teacher at primary school whom I had hated- to get just the right tone in my voice. 'My sentiments entirely. Now listen. Target for tonight is this building here.' He pulled a sheet from the blackboard and a gasp went up from the group. Margetts continued with a showman's lilt in his voice. 'Audacious? Certainly. Daring? Very. The very heart of that upstart's hold on the capital. Tonight we destroy - the Globe!' The assembled Baconians mumbled 'Honorificabiltitudinitatibus!' under their breath. I did the same. 'The Globe?' I repeated, trying to mix awe and daring in my voice, a voice that more naturally would have been one of outrage and disgust. Margetts smiled. 'All the world is a stage, sister. The Globe theatre is synonymous the world over with that charlatan Shakespeare. By destroying the Globe the name of Bacon will be on everyone's lips. It will be dangerous; the servants of the phoney Bard are everywhere and will try to stop us. But adversity, my friends, is not without comforts and hopes and with this act we continue to try and right the wrong of three and a half centuries! Okay, here's the plan...' For the next two hours Margetts outlined his plans f[or the destruction of the replica Elizabethan playhouse. There were to be three explosive devices, each set to go off an hour after we had got away. There would be a coded message to the police to clear the area as civilian casualties were bad PR. The BAC might be seriously misguided but they knew that public opinion was something that was very important to them; so far not a single civilian had been actually killed or hurt badly and they wanted to keep it that way. It was a simple plan and only required myself and the rest to act as lookouts. Margetts would be planting the charges and each new recruit, I learnt with a shudder, would be accompanied by a seasoned member. I was required to report in by phone to my contact at SO-9 at 9:00 that evening, but the overdue procedure didn't kick until midnight and by that time the Globe might be dust. I had only my initiative to help me. After the briefing I moved to the coffee machine where I was joined by Margetts. 'Nervous?' 'Yes.' 'Good. Gives you the edge. Sharpens up the senses. Stay close to Greene and you'll be fine. If all goes well I've got a got a very special assignment for you. Someone with your background will be of great use to the movement. How is your public speaking voice?' 'Not good. Why?' 'A war hero like you could be a great spokesperson for the group. The legal Baconians, I mean.' I fixed him with a steady gaze. I hadn't even collected the medal and hated talking about it. It was personal. Really personal. 'I'm no hero, Mr Margetts. I did what I had to do that day and coincidentally I saved a few lives. In conflict, similar acts go unrewarded every day.' 'Perhaps. As soon as you are blooded we can talk again.' Suddenly, I understood. 'You don't need me for this operation at all, do you?' 'Nope. I'm just checking on your commitment to the cause.' 'That is not in question.' 'Not after tonight. Excuse me.' I didn't get to a phone. No-one did. I asked Margetts if I could call my mother but he refused. At 11:00 that night the Chevrolet rolled to a halt in the dark streets behind the Globe. It had been raining and the wet streets were shiny with standing water. The dirt had been scrubbed from the air and London had a fresh smell that was rare in summer. We looked up at the new theatre in all its oak and thatch finery. The sfloodlights were off and it was surrounded by a shuttering fence without any guards to speak of. Margetts put a finger to his lips, murmured the word of the movement: 'Honorificabiltitudinitatibus!' and then signalled us all to don our balaclavas and follow him towards the stage entrance. Greene and myself were to bring up the rear; I had been armed with a 9mm automatic of dubious Italian lineage. I hoped I wouldn't have to use it. I pulled down my Balaclava and caught Greene looking at me oddly. With a jump of my heart I suddenly realised where I had seen him before. Myself and another LiteraTec had arrested him Pattempting to fence a rare signed copy of Fieldings' pseudononomously penned: An apology for the life of Mrs Shamela Andrews stolen from the Fielding museum. He had received a short custodial sentence and 200 hours of library service and that, I thought, had been that. He frowned, smiled and looked away again, pulling his Balaclava down over his face. I breathed a sigh of relief and followed Margetts across to the stage entrance where he swiftly disarmed the security guards and had them bound with cable ties on the floor. Greene and I were left to watch the main door and I watched with growing anxiety as the explosives crew disappeared into the Globe, their torches flicking and twitching in the dark as they struggled with the boxes of demolition charges. I looked up and noticed with a shock that Greene's eyes were boring into mine. 'What?' I asked him. 'I think we've met,' he announced slowly, 'did you and I ever-?' '-no,' I replied, quickly and positively. He shrugged and leaned out into the street and looked about. When he turned back I deftly pressed the muzzle of my automatic hard into his cheekbone. 'What the hell are you doing?' 'Drop the gun, Greene.' He didn't and I pushed the gun harder against his face. 'It's your lucky day. I'm giving second chances. Once more. Drop the gun or your mother has to attend your funeral with a closed coffin.' Even though I had never killed anyone or even come close to it, I knew that I meant it. The flush of excitement was exceptional; I hadn't felt it this strong since the Crimea and it felt Óuncomfortably good. My armpits prickled with the heat but my eyes and voice never wavered. Greene dropped the assault rifle. I kicked it aside and pushed him to the floor. I found the phone and dialled the memorised emergency number of the SO-9 fast response team. 'SO-9!' spat Greene from his position face down on the carpet. 'Filth!' 'What was that?' I asked, replacing the telephone but not keeping my eye or my gun off Greene's prostrate form. 'Bitch! 'Mrs Bitch to you, Greene. You're nicked.' 'I was right,' retorted Greene, 'You did f*** me once before.' The fast response team were there in twelve minutes. In eighteen the Baconians had been arrested and within forty-two, every device had been defused. Not a single shot had been fired. Margetts noticed me talking to an SO-9 field officer as his head was pressed against the bonnet of a SpecOps Buick prior to be carted away. 'It's not the lie that passes in the mind,' he said, staring at me with hatred burning in his eyes, 'but the lie that settles in the heart that hurts the most!' 'AH man that studies revenge keeps his own wounds open,' I reminded him, but Margetts simply smiled. 'You're one of us, Miss Next. Tell me that you believe in what you have been preaching. Tell me that Francis Bacon wrote the plays.' I took a step forward. 'Margetts, whoever wrote the plays and sonnets is immaterial. It could have been Kit Marlowe, the Earl of Derby or even Robert Greene for all I care. Being a Baconian isn't illegal; destroying literary heritage and murdering SpecOps officers is. So long, Conrad. I hope we never meet again.' They hauled him away and I leant against the wing of an Oldsmobile to catch my breath. I felt my stomach tighten and a hot flush rise in my cheeks. Before I knew what I was doing I had thrown up into a handy litter bin, much to the amusement of two young SO-9 operatives. The officer in charge took command and sat me in his car with a drink of water, something I was very glad to receive. I was just beginning to think about how wrong it all could have goneM when I was approached by a middle-aged man in a trench coat. He was tall and wore his hair long; He limped badly and one side of his face was frozen. He gave me a lopsided smile. 'Good work, Miss Next,' he said affably. 'Allow me to introduce myself. Commander Stratton, Head of SO-9, Southern division.' I stiffened slightly. I had heard of him often but never met him. His wounds, it was rumoured, came from an undercover assignment that had gone woefully wrong ten years ago; he still had spawl lodged in his head and had only just learnt to walk again. 'I understand you were recruited by Lieutenant Porkins? I nodded. 'Fine man and a good choice of horse flesh.' He coughed. 'Sorry, bad simile.' He smiled another half-grin that seemed a little bit too broad to be genuine. He proffered his good hand and I shook it gratefully". 'A bit of excitement for a LiteraTec, Hmmm?' I hoped my rankling didn't show. I didn't like being patronised, but I was willing to be patronised a lot if I could transfer out of the doldrums of the LiteraTec office. 'Thank you sir. I've enjoyed the experience immensely. I trust you found my work satisfactory?' Stratton smiled again. 'Of course. I will be writing a letter of recommendation to your superior back at SO-27; you'll be quite a hero when you get back there.' 'That's what I wanted to talk to you about, sir.' The smile seemed to drop from his face and he gave a sort of half-scowl. 'What do you mean?' 'I was wondering if I could be put up for transfer to SO-9 permanently, sir.' Another smile broke on Stratton's rather lugubrious features. 'How long have you been with the LiteraTecs?' 'Eight years,' I replied, 'but-' '-I think you'll find that SO-9 work is a lot more dangerous than just infiltrating Baconians. Have you ever been shot at?' 'When I was in the Crimea.' 'That doesn't count. Everyone gets shot at in the Crimea. SO-9 is quite different. Eight years with the LiteraTecs is a long time, Miss Next. Your record is exemplary. I am of the opinion that such obvious talents should not be wasted.' He smiled again without sincerity. 'The sort of work that SO-9 do is shitty and dangerous, Miss Next. It's not for women.' 'Except for now.' 'Exceptional circumstances,' affirmed Stratton. 'Believe me, I think you'll find that the LiteraTecs are a very stable SpecOps division to make a good career in.' I had to bite my lip. Stratton was a powerful man and whacking him on the jaw wasn't going to do me any good. knew I was as good as any of them but getting angry just placed you ten steps backwards. I had come across this sort of attitude before; None of the other SpecOps divisions regarded the LiteraTecs as real SpecOps; we were just given the badge to facilitate our work. In the most part it was true. Many of the LiteraTec operatives were college graduates who thought a Browning Hi-Power was a vigorous stanza by a Robert of the same name. So I swallowed hard and said instead: 'Thank you very much sir.' ¨ Elmo yowled at me quizzically when I got back to my flat. I had missed his supper and he was just toying with the idea of expending some energy catching his own when I walked in. Lucky for him I came home when I did. Knowing Elmo he would probably have been beaten senseless by a gang of mice. 'Sorry I'm late pal. Got caught at the office.' I poured him some cat food and slipped off my shoes, removed my jacket and flopped on the sofa. I should have been happy at the day's work but I wasn't. It hadn't led anywhere and that hurt. I had done my time. I deserved a break. It was a depressing comedown after the success of the evening. I tuned into an empty channel on the TV and watched the snow on the screen, lowering the volume so just a dull hum filled the room. I liked it like that. Even when I slept I liked to hear some sort of noise to remind myself that I wasn't alone; silence signified death and inaction. There were three messages on the answer phone, one to myself to remind me that it was my Mother's birthday tomorrow and another from Boswell congratulating me about the Baconian result and telling my that I could have the day off tomorrow. There was another from Boswell's deputy Susie Flanagan who told me to ignore Boswell's message and take a week off instead. It was so typically LiteraTec. I couldn't sleep so tidied my already tidy flat and when that paled I puÑlled the dust cover from my painting. I stared at the half-finished canvas, mixed up a small shade of greeny-blue and dabbed the canvas delicately. The painting responded to my touch, the surf in the picture that much more alive, the wreck on the reef that much closer to reality. I painted until the morning. You got this far? Wow. C Jasper Fforde 1995 |